Forgive my brutal translation (we’re in the wee hours), but there is a ghazal that goes:

‘ever since I heard you were far away

I feel like going far away’

&

‘on their street they’re nowhere to be seen,

but I feel like just walking up and down it’

As a form, the ghazal’s most famous feature is the refrain at the end of the couplets. In this - it is the words ‘jee chahta hai’, which more literally translates to something like ‘the heart wants to…/desires’, which (while more poetic), I couldn’t put at the end of the couplet because it wouldn’t make sense in English. To keep the Urdu refrain at the end, would look like this:

“Ever since I heard you were far away

going far away, the heart wants to

&

On their street they’re nowhere to be seen

just walking up and down it, the heart wants to”

Clunky and unpublishable sure, but it gets at what the Urdu is doing in a different, perhaps more direct way. I find literal translations extremely useful in painting a picture of what the original language looks like in a way that a ‘good’ translation can’t, or sometimes won’t do. Even the other refrain,

“gham-e-dil sunane ko ji chahta hai”

The translation would unlikely tell us that gham-e-dil (sorrow-of heart) is different to ‘dil ka gham’(sorrow of the heart).The fact that Urdu has these compound phrases that turn the heart’s sorrow into a kind of noun, (linguists will tell you the correct terms I’m sure) is lost to a translation.

This short, simple (even diaspora frauds like me can understand it without much trouble) ghazal is filled with these emdearing couplets. Perfect examples of not only Urdu’s natural poetic weight, but also the Lover’s perceived madness. A love that is ever-difficult to explain, with poetry often making the most fruitful attempts. Of course, it is beyond the rational. There is no rational reason why you’d walk down the street your beloved lived on, but it makes sense to the heart.

Across cultures, there is a way in which death often makes this plain to us. The reason why my mother keeps her uncle’s blazer hung up behind a door doesn’t require theorizing or lofty explanations. It is akin to walking needlessly down their street every now and then, to holding a soft relic of a beloved, to pilgrims who just want to sit near the beloved of God, peace and blessings be upon him. Urdu, and the ghazal in particular are ideal vessels for love. The couplets, the repeated refrain, the universality of longing - all make the form easy to internalise and memorise for so many.

It isn’t just the poetry (which I have limited access to in any case - my capabilities in English are far beyond what I can read, and definitely express in Urdu), but even hearing Urdu spoken sweetly is moving in a way that is difficult to explain. Urdu may not be my most spoken language, but it is, and of course always will be, my first. Perhaps it is this link to childhood, to the sea-like purity of that time, that makes Urdu so irresistible to me. There is a satisfaction I get in being able to express myself as perfectly as I wanted to in Urdu, that goes beyond just attempting mastery of a language, but something that feels like I freed a caged bird.

I think of city children in Pakistan using English so casually. How this place of a language so astounding - is losing Urdu (and others) in its most ‘educated’ classes. What it says about this education is as plain as day, but if English keeps you eating, and Urdu doesn’t keep the lights on, what do we expect people to do? While introducing the recently deceased Zia Mohiuddin, a host once remarked that Urdu has become like a zoo animal, that people come to see in gatherings such as his.

This phenomenon is true across the border - as a new arrival from Rajasthan lamented to me, and true in the Arab world as my Hamawi father-in-law tells me. Bollywood stars making entire films in Hindi and Punjabi but doing their interviews in English, many countries likely have similar dynamics. In place of rigorous analysis of the linguistic norms of postcolonial states, as ever, I welcome reading recommendations if you have them.

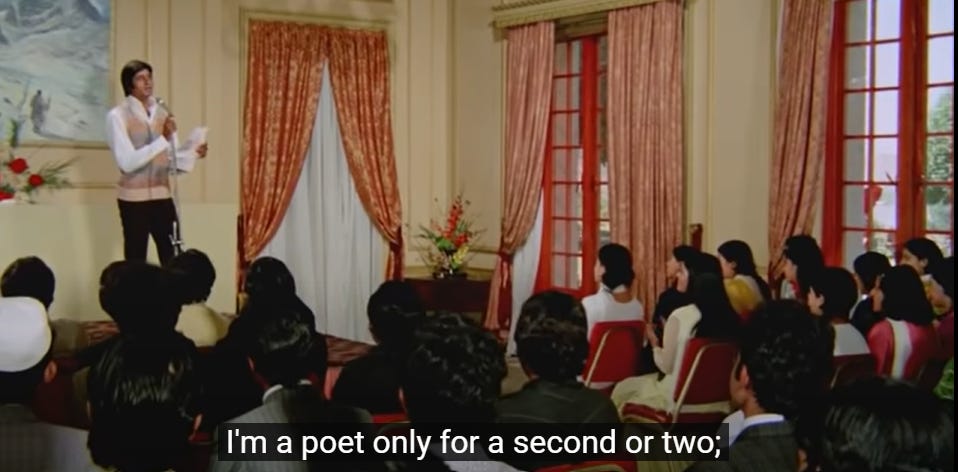

What also stands out in Urdu poetry culture at large, and what you’ll see in the video, is the delivery and the vessel for the poetry. Often sung, and often ‘spoken’ aloud to a crowd, there is no distinction between Poetry with a capital P, and ‘Spoken Word’ with a capital S and W. I sometimes think how impossible it would be to try and explain what ‘spoken word poetry’ means to my grandmother. It isn’t specific to Urdu, but I would imagine many cultures would find this distinction nonsensical too.

There’s also the settings often associated with poetry in that part of the world. The idea that people would dress-up to go and sit in beautiful surroundings mostly in silence and listen to poems, is charming.

That’s not to say I don’t enjoy the cafe-backroom style that I came up through, but the level of weight (read funding) given to poetry culturally is indicative of where that place’s priorities are. With news of poetry leaving curriculums, and the constant battle for funding that practitioners have in the UK, it is clear where we are.

Some news - my film Muriid is showing at Rituals & Ruptures on the 30th of July, and its free. I’ll also speaking on a panel about faith on film at 630pm, God willing. Come through and say hi.

As ever, if you enjoyed this, please do share with loved ones you’d think would enjoy it too.

All the feels